Worlds and photos below by Jason Lee

Scroll to bottom of page for discount rates available as Vitruvian closes out its current location (claim by 1/1/24)

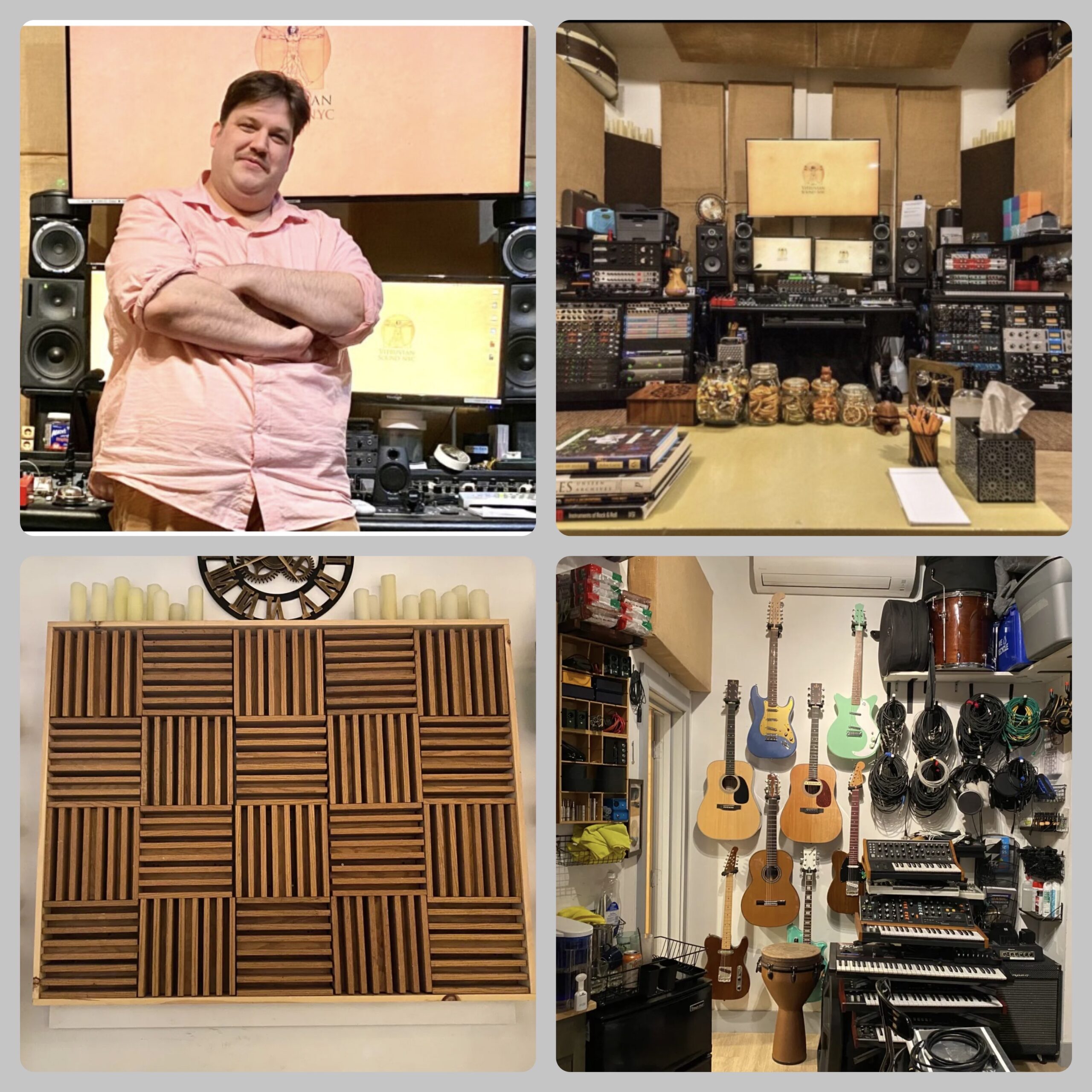

Upon entering the recording facility known as Vitruvian Sound—located off an L train stop in the L-for-liminal zone between Bushwick and Ridgewood, i.e., Brooklyn and Queens, and yes liminality is gonna be running theme—the eye is greeted with a riotous array of stimuli including a dozen or so guitars hung on the wall, multi-tiered stands of analog keyboards, towering rack units of vintage signal-processing modules spanning the decades, shelves full of effects pedals and reel-to-reel-tapes and cables plus the requisite mixing board, monitors and speakers not to mention the vocal isolation booth tucked away in the back and the sound diffusion panels hanging over the couch which once resided in Andy Wallace’s 1990s-era studio bearing witness to his mixing work on such obscure diamond platters as Nirvana’s Nevermind and Jeff Buckley’s Grace the latter of which he also produced…

…which given Virtruvian Sound’s relatively modest dimensions makes it doubly impressive cuz it doesn’t feel cluttered probably due to everything being put away in its designated place and the feng shui level of attention to wall and shelf space arrangement thus making the studio both a Taoist’s and a gearhead’s wet dream and it ain’t for nothing its sole proprietor/engineer/producer Stephen Kurpis has been given the nickname “Gear Daddy” tho’ it’s also due to his side hustle producing audio books with the help of an ever-growing array of voice actors—erotica literature in particular—with titles like Love You So Hard and Brutal Beast and Dirty Therapy (“Ben and Landon have some unique ways of treating their patients. I shouldn’t succumb to their panty-melting smiles…but I can’t get enough!”)…

…and what’s more the studio’s a great hang-out pad too which I’m guessing doesn’t apply to your average corporate recording facility or cramped DIY bedroom studio setting seeing as Stephen has somehow made room among the many objets du musique for a well-appointed bar and coffee/tea/biscotti station and if you happen to drop by you’re likely to be offered a mixed drink by the engineer-cum-mixologist who breaks down the beverage’s contents like he’s mixing sound for a client and then there’s the 10 varieties of Cholula hot sauce neatly displayed in a small wire container afflicted to the wall and ditto for the three glass jars of sugar helpfully hand-labeled as “real ass sugar,” “raw sugar,” and “cancer sugar”…

…all of which seems to indicating both a Hannibal Lecter-level of meticulousness (if you think about it, good recording engineers are like good serial killers: you gotta be passionate if not borderline unhinged enough to tap into and even amplify the extreme emotional states inherent in most music but painstaking enough to keep track of and organize dozens-if-not-hundreds of tracks and takes, plus psychologically detached enough to translate heightened emotional expression into a technical puzzle to be solved and vice versa, all the while keeping the seams from showing much like a serial killer hiding away the bodies or in other words you gotta get the balance right between extreme ontological states) but at the same time Stephen’s a fun, non-uptight dood with an irreverent sense of humor—witness those sugar labels—plus a warm, gregarious nature and a ready laugh and amusing anecdotes at the ready…

…which has been an object lesson of sorts in the Audio Engineering and Record Producing Arts—an object lesson that first began taking shape at a Deli-sponsored producers’ roundtable no less also featuring indie-rock-of-all-stripes production wunderkind Jeff Berner from Brooklyn’s very own Studio G and Grammy-winning, that’s right Grammy-winning, engineer/producer Denise Barbarita who works out of her own MonoLisa Studio in Long Island City…

…who all discussed the necessity of promoting what one could call “organized chaos” where impulsive choices and chance happenings are just as vital to producing a vivid, memorable sound recording as having a vast array of plug-ins or being a little too ready to quantize a beat or autotune a melody (tho’ we do love us some T-Pain) and no wonder there’s a poster on the door of Vitruvian that reads “FIX IT IN PRE!” versus the standard “fix it in post”…

…cuz from all indicators one of the biggest perils faced by artists making a record on a limited budget or heck not on a limited budget is the tendency to overthink the process itself and get trapped into an endless cul-de-sac of digital selection stress whereas certain self-imposed constrains can be conducive to the creative task at hand (exactly why Stephen offers only three varieties of sugar we suppose when there’s dozens to be found at the supermarket) which is why making a record is often such a Zen task to undertake…

…not to mention attempting to smooth out every wrinkle and perceived imperfection in the midst of recording or after the fact whereas it’s exactly those rough edges that can give a recording its edge or in other words make the music feel alive andvital cuz a slight bit more often than we’d like to admit we find ourselves listening to a band on record—bands at all levels of the “ladder of success” we should add—who we witnessed make a roomful of people jump around and slam into each other or conversely sent into a shared state of ecstatic reverie where the music removed from this context suddenly comes across as rather frictionless which is a sad, sad thing indeed…

…but why endure anymore of our pontificating cuz we were lucky enough to interview Stephen Kurpis little while back and he shared his thought on this and others subjects drawing on expertise and experience that we’re totally lacking in and oh by the way if you happen to like the cut of this engineer-producer’s jib and if you happen to be planning on making a record in the near-to-mid-term future then Vitruvian Sound has a Christmas Gift Just For You in the form of a discount that can be claimed in the next couple weeks if not maybe a little longer and redeemed in the next six months or so before they pull up stakes and move to another nearby but slightly more ‘lux location in partnership with some other engineer-producer friends so read on dear reader…

‘

On early signs of becoming an audio engineer…

I was always that kid that played with Legos and liked pulling shit apart and figuring out how things worked.

My mother used to get cluster headaches, these horrible fucking migraines. When I was 5 or 6, she’s knocked out on the in the living room with a headache. She’s cognizant, in case I fall or something like that, but not paying close attention to me. So my grandfather comes home. We lived in Yonkers—the old school Italian thing of your grandparents living in the basement apartment—and when he comes home I’m behind the television. So he’s, like, “what the…what are you doing behind the television?” And apparently I’d cut the cable line with scissors, and I’m staring at it. I asked him why you couldn’t see the pictures in the cable line. So at that young age I’m already trying to figure out how the TV works.

When I started getting into music I continued being interested in electronics. My dad had decent corporate jobs but was also a little cheap because he’s an accountant. He would bring home these old computers from work and then say, “all right, do some research. I’ll talk to the tech guys, we’ll order you new parts.” So I was rebuilding computers at 12. I learned to solder from a friend’s father who was an electrical engineer by trade; which was useful when I started playing guitar in local bands.

We’re in New Jersey at this point. Western New Jersey, about an hour away from New York City. This was early in high school, early post-9/11 era, and you could still get into shows with fake IDs. The police were too busy harassing Muslims to mess with someone like me. My first club show at 16 or 17 I snuck into the Knitting Factory to see Blonde Redhead. It 2002 or ’03 and it fucked hard.

Itinerancy ain’t for me…

A working band has to travel to make any money. But I didn’t even like traveling as a kid. Family vacations were always just kind of boring to me. So at that time I wanted to be a session musician more than anything else. I had no interest in being a fucking rock star or being famous. I wanted to be sitting in a studio tinkering endlessly.

I don’t play guitar anymore. I’m too busy here and I get enough creative fulfillment with my studio work. I sold my guitar about two years ago, during the pandemic. I felt guilty about holding onto it when I know I’m not going to use it, or for sentimental value, even more because I’m left handed and it was a lefty guitar. It was just hanging on the wall and no one else could use it. At the end of the day a guitar is just a tool for musical expression. I’m not going to cry over it. Maybe I teared up a little bit when I had to sell my favorite hammer, but I’d rather someone else use it.

First steps…

At end of the day, session musician work was unreliable. With my technical background, I decided I wanted to move into engineering work. I’d only made recordings with shitty little 4- or 8-track tape machines up that point so I went to a trade school, a quick program to learn Pro Tools. And then ended up doing a bunch of the typical multiple internships for years including work at a really big jazz-oriented studio. I remember once one of the engineers screamed at me about something, and then 7 or 8 years later, he’s inviting me to be a partner. So it’s the full circle thing.

I also apprenticed for the Blue Man Group for a while which was cool. Only 3 or 4 months, but it was a fun gig. I learned a lot there and still have the studio room. They made me paint myself blue for every single studio session. Even though I was just running cables, you had to paint yourself full blue. But we only had to go half-blue, paint half your face, when you’re still in training. Ccan’t be full blue right away, you have to earn your stripes.

During that time I was freelancing at a bunch of places. I worked my way up in one studio and then finally just rage quit. I didn’t like the culture, didn’t like how the equipment was maintained and how little effort people put into developing their skills. It was very much top-down “fuck you” facility vibes.

The birth of Vitruvian Sound…

I really dislike those places and the culture. They combine all the bad things of the art world with all the bad things of corporate office culture. So I left and took a bunch of clients with me. I started Vitruvian Sound in June of 2017, located off the Jefferson stop of the L train in a tiny carpeted room that was 200 or 300 or square feet, with two booths and one tiny control room, while still working at a couple other studios for bigger clients.

After two years, I moved to my current location here at 10-01 Irving off the Halsey L stop. Now I’m entering year five which will be my final year here. I’ve kept expanding into doing a greater variety of work, adding more shit that’s stacking higher and higher which will soon be taller than me. I’ve introduced more audio post work, voiceover work, audiobook production, expanded horizontally more and more.

Hopefully in the next year or two I’ll be part of a larger collective with some partners—we’re currently making our plans and scouting locations. We’ll have a larger space that’s even more efficiently designed and run. Working alongside a collective, I won’t have to raise my rates. So that’s the journey so far. It hasn’t killed me yet.

A middle ground for the middle class musician…

There’s a big underserved market in New York. Even as the middle class shrinks, there are middle-class creatives that aren’t catered to like they could be. It’s the stratification you see in the economy in general. But they’re still out there and still need professional services. It’s still possible to have all the fancy studio whiz-bangs on offer and help foster and grow the middle-class of working musicians. Otherwise they’re largely at the mercy of knowing the right person—being friends with someone in a big studio where maybe you get a decent overnight rate, if you’re lucky, six months or nine months down the line.

What I can offer these musicians is a middle ground between polished “professional” and accessible, plus help foster effective decision-making which can be a challenge in the digital era. Add on to that the malfeasance and sometimes malevolent ways of bigger studios who only encourage you to defer decisions to expand their billings.

Because if you’re waffling back and forth forever, spending time trying out all kinds of things with little direction, you can slowly get bled out. Whereas if you work with someone who’s excited for what you’re doing and knows what they’re doing, who’s willing to give a kick in the ass when it’s needed, it makes all the difference. It’s about finding that balance.

Get the balance right…

Any kind of system should be like a skeleton. It should have some rigid points but also be fairly flexible and support everything around it. Otherwise, you’re just slithering on the ground because you have no shape. Or you can’t move at all because you’re one big giant inflexible rock that can’t move at all.

You need a balance between the two. I think that’s really really hard to achieve in New York. Then there’s the decision fatigue that comes with digital recording with all the companies making claims like “if you buy this piece of software, you’ll be a pro!” I mean, “all right dude!” I’ve got a bunch of software and it sounds fucking great if you want to use it. But there’s always the danger you’re hearing the results through the filter of your own ego and your own insecurities, or your own overconfidence, if there’s no one there to help maintain a state of equilibrium.

Someone who’s not egotistically invested, but who also gives a shit; it’s externalized for them. It’s similar to how you can’t see the back of your own head, so you never know if there’s a big ol’ bald patch back there. Mirrors aren’t perfect. They can distort. So it helps to have an external presence, someone to say, “I think you’re missing this here.” Someone to help you fill in the blanks and to recognize what still needs work and what doesn’t necessarily.

Creative divisions of labor…

For a lot of musicians it’s already tough staying focused on the creative side—channeling those spontaneous, explosive moments that make a performance stand out—especially when they also trying to focus on dialing in the sounds themselves and micromanaging all that kind of stuff. At a certain point, you just want to be a MUSICIAN.

And it’s already tough being a musician on the financial side of things. Like I said before you have to tour to make money. So why spend thousands of dollars on recording equipment that’s going to sit unused in your rehearsal space most of the time, not to mention learning to use those tools effectively. From an economy of scale standpoint, you’re better off buying instruments and gear that you’re going to use on a regular basis, and then parking up in a recording studio for however long it takes when the time comes with access to all my shit—or whoever’s shit—for the economic efficiency even apart from the creative side.

At a certain point you’ve got to have a bit of emotional detachment—see the forest for the trees—and separate the thing in itself from what it helps you do, and create in terms of your end goal.

The second-hand gear economy…

Everything in this room gets used—even if it’s only once or twice a year—and I know how to use it. I collect a lot of things you’re not going to find anywhere else. I’ll go dumpster diving for shit. These diffusion panels came out of the studio where Andy Wallace was mixing in the ‘90s—including records by Jeff Buckley and Nirvana’s Nevermind for starters—because I helped someone sell some gear who was an assistant there. And they said, “hey look at this just take whatever you want” except it was literally in a dumpster about to be tossed.

So I had to go back that night in the rain because it was all being thrown out the next day. I like finding stuff that’s funky and weird—not super high-end but fucking gnarly and vibe-y. Even if it’s not the most modern of workflows. For example I really like these Lexicon PCM 41 digital delays because they’re “shitty” digital with a weird kind of early ‘80s low-fidelity to them.

Say you want a delay setting that’s 18 milliseconds—but on this unit here’s 13 milliseconds and the next setting is 26. So how do you get it? Basically, you have to fish around on this multiplier control and I love it. You get somewhere close to 18. And it’s same thing with this rate control. On certain things like this if I didn’t want to fight something, I would just have a digital version of it. On this…I have to pull it and fight it like some BDSM scene.

Perfectly flawed perfection…

But it’s the flaws in equipment, and in people, that are the fucking personality. Laboring over “perfection” too much just means you’re going to end up with something second-rate. Real perfection comes from finding that perfect flaw, appropriate to the context. The same idea can be applied to sound patches and instruments. I don’t have a piano here, we hopefully will in the next studio, but I do have piano players who like me because I can actually get MIDI pianos to sound good.

The trick is making the sound “imperfect” in just the right way, because otherwise, you have an okay sounding MIDI piano patch but everyone uses the same thing knows what it is. So I have this little trick, if you want something to sound real, just fuck it up a little bit…It’s what like and god does to you to test you and make you more into a person…

I add second piano, two different piano patches layered together and one’s pitch is distorted. So they rub weird together. Better to make it a little “off” so it’s more resonant, just like a real piano where piano tuners tune the strings to be the slightest bit out of tune in technical terms. Plus it gives the piano sound a unique personality, just like any real piano has, or real musician has, because everyone’s different.

Keys to effective communication and f*cking s*it up…

We want to fuck shit up in a way that’s cool, that’s interesting, and serves the project. It’s a lot of catering yourself to the person, but also training them in a way to communicate. I’m catering myself to the client’s perceptions—while retaining my own personality, views, processes and filters—but clients can struggle with linguistics, finding the words to describe what they want. And if they use technical terminology, it doesn’t necessarily translate to how engineers would use those terms. I like it better when people don’t try to talk to me technically, when they’re more subjective instead of trying to be too clinical.

I have one client who’s great, he’s a photographer, so certain things from that specific vantage point are helpful. Like if he describes a sound as “grainy” it doesn’t mean what it would mean between audio engineers. There’s a whole new perspective that gets opened up there. Increasingly I’ve encouraged him, “Why don’t you speak like a photographer? Explain things to me as a photographer. Explain your craft to me in relation to what we’re doing.” Worst case scenario, that opens up a good two- or three-minute conversation, “Okay, what do you visualize? What does ‘grainy’ mean to you? What does ‘purple’ mean to you?” And so on. It opens up the discussion instead of shutting it down which is crucial in so many ways.

Another client I’ve really hit a stride with are the trio Bandits On The Run. We’ve been working together for five or six years and been friends for longer. They’re theater kids in a pop-folk trio that’s gotten a little heavier and more experimental as they’ve gone on. We’ve developed a great workflow. Even though there’s four of us in the room and we’re editing vocals, it’s a really decisive process which comes from everybody caring about each other, respecting each other, and recognizing what everybody’s good at. I’m really good at this, I’m okay at this. With X, Y, and Z, tell me if I’m fucking crazy. Anyone says anything, I’m going to shut the fuck up and fuck off. Anything where there’s a point of disagreement, everyone feels cool discussing it.

That’s having real artistic confidence in your craft—when you know your limitations you ask for help, insight on other things. You realize that you’re one part of a larger thing where there’s no grandstanding ego, acidic disagreements, toxicity, or anyone being overtly dismissive. It’s true on the production side too. It used to be, because they were theater people, the vocals were really cranked. They were a little loud for me, but it was poppier stuff and I’m an indie alt-rock asshole. But on their latest projects, you know what, I want the vocals a little higher now. Our influences have rubbed off on each other a little bit. We’re both balancing each other out.

Multidimensionality is the mix…

So you have to be a little bit of a chameleon with everyone—maintain your separateness, but also be able to contribute as a holistic member. Sometimes it helps when you can say, “well, this isn’t my thing,” because I’m a little outside of what you’re doing. But as long as I can learn along the way it works. It’s all about workflow and communication, connecting with people, so long as people can express what they like about something, and show me some core of what it is they’re going after.

One of the things that’s influenced my viewpoint on audio engineering are techniques I’ve learned about from Walt Disney‘s multiplane camera. It was used in all the big-budget animated films they made around the 1940s and ‘50s like Bambi, Snow White, all the classics, where there’s such a realistic sense of depth and perspective. They would have 4 or 5 separate planes of background cel animation. And there’s a camera, mounted vertically, that shoots down from above the multiple planes. And they’re moving these 4 or 5 planes not only at different speeds, left to right as a pan, but also in relation to each other.

So you create this incredible sense of three-dimensional depth. You can watch the intro scene of Bambi with the scrolling forest for example, where they’re shooting down through five different cells of animation for the background. And that’s parallel to how you record drums. A close mic, an ambient mic, a distant mic, room mics. You layer distortion, you layer in other things. Again, it’s about getting the balance right. Finding that balance between dimensions. What I do is I sculpt with sound. That’s the pretentious way to put it. I literally like to think that I shape air molecules so they create a visual image. Some weird kind of synesthesia.

************

Discounted rates special offer: Closing sale for recording at Vitruvian Sound’s current location

Contact: Stephen at stephen@vitruviansound.com

1) 25% off all bulk hour purchase plans with my direct engineering labor.

2) 20% off all bulk hour freelance engineer bookings.

3) 15% off freelancer half-day, full day and week blocks.

Utilization term will be reduced to 6 months starting on January 1st, 2024 and ending July 1st, 2024. No more than approx. 750 bulk hours will be sold in order to ensure access to the studio, and the monthly utilization cap will be increased to 30 hours. Installment payment plans for bulk hour purchase will remain as a four (4) payments placed on a 90-day cycle. Additional 5% discount will be applied to bulk-hour purchases that are placed with a single lump deposit.

Limited to music production services clientele. Sale officially ends on January 1st, 2024.

************

Owner Stephen Kurpis is a veteran of the Manhattan large facility recording scene who has recorded voice-over for Nickelodeon, audiobooks for Simon & Schuster, VR for The NY Times, and live streamed events for The Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. As an engineer, he’s recorded jazz, classical, hip-hop, folk, rock, and Broadway cast recordings; highlights being Philip Glass, Spin Media, and Audiomack. He’s spent time as an educator and studio manager while continuing to build his freelance base. The studio has been designed to embrace the future of audio production in an increasingly fluid and dynamic creative environment without the sacrifice of quality.